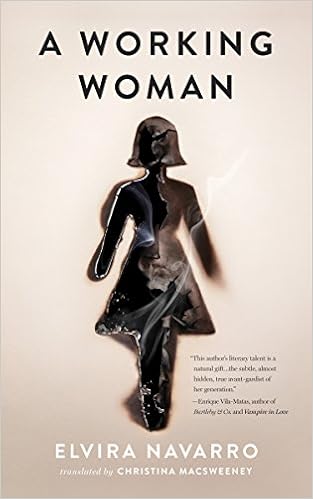

Elvira Navarro, A Working Woman, Trans. by Christina MacSweeney, Two Lines Press, 2017

Globally acclaimed as a meticulous explorer of the psyche’s most obscure alleyways, Elvira Navarro here delivers an ambitious tale of feminine friendship, madness, a radically changing city, and the vulnerability that makes us divulge our most shameful secrets.

It begins as Elisa transcribes the chaotic testimony of her roommate Susana, acting as part-therapist, part-confessor as Susana reveals a gripping account of her strange sexual urges, and the one man who can satisfy them. But is Susana telling the truth? And what to make of Elisa’s own strange account of her difficult relationship with Susana, which blends her literary ambitions with her deep need for catharsis? Is this a true account of Elisa’s life, or is it the follow-up to her first novel that she has long been wanting to write? In one final surprise, A Working Woman concludes with a curious epilogue that makes us question everything we have just read.

With her penchant for finding the freakish side of the everyday, her precisely timed, mordant sentences, and her powerful, innovative style, A Working Woman confirms Elvira Navarro as “the subtle, almost hidden, true avant-gardist of her generation” (Enrique Vila-Matas, El País). A Working Woman masterfully uncovers the insecurity lurking just beneath the surface of every stable life, even as it points the way toward new concepts of what the novel can be.

“This author’s literary talent is a natural gift… the subtle, almost hidden, true avant-gardist of her generation.” — Enrique Vila-Matas

“Elvira Navarro is an enormously gifted and disturbing young writer with an unusual eye for the bizarre; she captures personal fragility with deceptively detached prose that stays with us like a scarring incision.” — Lina Meruane

“Navarro is one of Spanish literature’s most interesting contemporary writers.… A Working Woman represents a major leap forward in her work.” — Perfil

“The book surprises the reader. . . . Disconcerting in the best possible sense.” — El Cultural

“The singular thing about this novel is…the narrative voice.” — El País

I heard great things about Elvira Navarro's A Working Woman (Two Lines Press) when the book published in Spain a few years ago, with praise by authors such as Enrique Vila-Matas. I later spoke with Christina MacSweeney when she was working on the English translation: she confirmed this was a book I needed to read.

A Working Woman tells the story of two women living together in the outlying districts of Madrid during the last European recession. The book invents a language and a structure to portray the outskirts of the city—and the characters' job insecurity—like no novel has done before. It speaks intelligently and originally about mental illness, tracing the relation between insanity and modern economics.

Navarro is one of the most daring writers in the Spanish-speaking world, and MacSweeney has done an amazing job in bringing the originality of her voice into the English language. - Daniel Saldaña París

I’m increasingly fascinated with characters who buy out of the system, both in literature and life. I wrote my first book about this very thing as it relates to the Mexican drug war. Elvira Navarro’s A Working Woman (Two Lines Press) touches on this as it relates to the Spanish economic crisis. But I also talk about the very real characters, too, with my childhood best friend who isn’t a writer but a DC insider who seems just as confounded by the mechanizations of his city these days as everyone else.

We talk about our old things—the Spurs, personal/professional life, marriage, music, books—but lately we’ve been talking about the news a lot like (I imagine) everyone else. It used to be that you could forecast certain things: elections, poll numbers, pledged money, persuadable voters, approval ratings, etc. My best friend made his career on big data. But what should you do when people buy out of an old system en masse? When people cleave off and cleave out an alternative truth and reality for themselves?

In reaction to the current anti-realpolitik, I can’t help but wonder if I’ve done the same but to the other extreme. To root yourself in reality in 2017 is, to some extent, to rage against the post-truth era. The truth is now radical, which is weird! I like to think of myself as rational and self-admittedly not very edgy. Of course, I believe I’m in-the-right: I’m a staunch feminist. I believe in social justice. Being a professor, I believe in empirical and peer-reviewed research and the truth. In sum I believe in, you know, not being a bad person. And only recently, in the wake of certain conversations with my childhood best friend, I’ve come to wonder: is that because I can still afford to buy into that system? Because, in some sense (however small the gains might seem to me), to the people who bought out of the system, might I be a perceived winner of the old status quo? Is it that I can still afford to be not a bad person? Moreover, would I feel the same had the system failed me?

I’d like to think, yeah, I’d still be into not being a bad person. Though in heeding the realities of 2017 I can’t not look away from those characters who opted out of that seemingly rational decision—rooted in human decency—not to be bigoted, not to be racist, not to be misogynist. In a sense, those who opted out of being a decent human being. But then what is that anymore? And is that definition centered?

Elvira Navarro’s A Working Woman, translated by Christina MacSweeney, interrogates the psyche of characters mired by the Spanish economic crisis and the realities and lies they build around themselves in search of catharsis.

The novel is narrated by dual unreliable protagonists, Elisa and Susana, who become roommates at the urging of Elisa’s friend, German, who plays a key role in the disintegration of their relationship toward the end of the book.

The novel opens with Elisa’s disclaimer that “this story is based on what Susana told me about her madness. I’ve added some of my own reactions, but to be honest, they are very few . . . ,” which keys us into Elisa’s own penchant for reality distortion, for rewriting the events as they actually happened. Perhaps, as a form of escapism and/or longing for the literary novel Elisa wants to write or perhaps as a way to take Susana down a peg if only in her own mind.

By the end of the book we’re not so sure if Elisa has crafted this narrative from her own reality as a struggling copyeditor at a large (but uninspiring) Spanish literary press, or if all of it (her entire subjectivity as presented to us) is just another alternative reality that’s actually part of her novel-in-progress, which we know she’s writing—a simulacrum of her true life, a coping mechanism alternative reality which she uses to deal with her personal traumas of finding herself further and further outside of the geographic valence of her old pricey apartment at the heart of Madrid, which is to say further and further outside of high-brow society and definitely further outside of economic security amidst a shrinking book market that rarely pays Elisa what she’s owed on time.

From Elisa’s opening lines, we jump into first person Susana who, presumably using Elisa as a therapist or sounding board, opens up (but not really because she’s unreliable) about her frustrated sexual desires and her relationship with Fabio, a man who has dwarfism, who fulfills them. It becomes apparent as the book progresses and Elisa’s voice begins to dominate the narrative that we realize Susana is a pathological liar unwilling or incapable of any true intimacy, which frustrates Elisa who wants to know the truth about this woman she’s living with.

We come to learn, via Elisa, that Susana lives in a curated present informed by an imagined past. It’s no surprise this tendency toward curation is what ultimately leads Susana to an almost accidental career in visual art toward the end of the book. Susana’s success in part widens the rift between the roommates, though the full realization of this decayed interpersonal fabric is foreshadowed in Elisa’s sense of dread that’s reflected throughout her sections of the book.

Elisa finds herself fascinated with the decay of the neighborhood around her which is located in the outskirts of Madrid, a place where historically and presently the undesirables of the city have been pushed out to live. Nearby are the ruins of a former prison Elisa keeps returning to. And the neighborhood itself becomes a kind of tether back to reality and a reminder to Elisa about the unsustainability and inescapability of her life that’s constantly under assault from the financial demands of life, which are actually very modest.

For both characters, to disengage from reality is to survive. To confront reality is to exacerbate their psychoses. I think deep down, as they’re living it in the moment, both Susana and Elisa know this disengagement from reality and each other is irrational but necessary. And the tragedy when they finally do bridge the gap between them—when they have to cooperate within the parameters of a mutual reality—is that their fears are not only confirmed but realized when everything comes unraveled. Reality undoes them. And nothing is ever the same again.

Bringing this full circle, I think what fascinates me about this book is that I’d never thought about post-truth as a coping mechanism before. It brings up the question: how much of our dignity is tied to the way we interface with reality? And what becomes of us when reality does not validate who we tell ourselves we really are? Or who we should be?

Navarro’s book was originally published in Spanish in 2014, long before the 2016 presidential election. So, it’s not as if the idea of post-truth and reality warping in A Working Woman are in conversation—they’re not. But I also think there are parallels that can be drawn between the populist moment we’re in today and, say, the things that have given rise to populism across Europe in the wake of the financial crises there, especially the Spanish economic crisis.

Reading through A Working Woman, Elisa and Susana are characters whose chaos definitely affects the way they operate in the world, but they have tendencies to implode into themselves rather than explode. I am haunted by these characters, especially when I think of the very legitimate leftist populist gripes concerning the capitalist exploitation of cheap labor (Elisa) or the isolation and desire for human connection experienced by workers heavily involved in the gig economy (Susana). But what is the left’s relationship to post-truth? I think we have one, though it looks something more like that implosion than explosion.

We now know that economic insecurity has played no small part in the shift into post-truth. And part of what I wonder now is how much of my own anxiety about the current era comes from the fact that so many people have bought out of the system in which I, like I suspect many readers here, were winners (if only perceived winners) of that system. Readers, literati, mostly college-educated, employed, probably middle-ish class. Does that make us losers in the post-truth era? The reality of that has yet to unravel. - Daniel Peña

A Working Woman is a three-part novel. The long middle part has narrator Elisa Nuñez describe her life during the time when she has a roommate, Susana, but before she gets to that, in the first part that takes up about a fifth of the novel, she offers a (rather sensational and quite bizarre): "story of what Susana told me about her madness", recounting a time in her life some two decades earlier. In her younger days, Susana solicited sex via newspaper ads -- a reaching out for company and way of engaging with people, too -- and entered into a relationship of sorts with one of those who responded, the homosexual dwarf Fabio.

Elisa is a proof-reader and sometime writer, and a while back she even published a novel. In presenting Susana's story, she notes originally: "her narrative was more chaotic"; she also adds, in square brackets and italics, some of her own reactions to parts of the text -- in other words, she shaped it, and inserted herself into it, in part, as well. As, of course, she then does more clearly in the middle section, which is entirely hers.

The second part of the novel begins with a short story that Elisa published, in a now-defunct Spanish newspaper, before then coming to the main storyline, as Elisa describes the months Susana shared her apartment.

Elisa had gone through three temporary contracts at the publisher she worked for, before being "converted to" an independent, making too little money -- and her employer in arrears with some of what she's owed, but cleverly keeping her in line by paying her for whatever the urgent books of the day are. Elisa can work from home, only occasionally venturing to the publishing house offices.

The now forty-four year-old Susana, back in Madrid from seven years abroad, is recommended to Elisa by their mutual friend Germán, and quickly spreads herself out in the apartment, encroaching on Elisa's space in ways she isn't used to. Susana's strange habits -- such as disappearing for five days right after moving in -- grate and irritate, but the two do form a kind of friendship. Susana has a Dutch boyfriend she continues to keep in touch with, but doesn't mention family and seems to have, at best, superficial friendships -- much like the relatively isolated Elisa.

Economic hardship is a prominent backdrop throughout most of the novel. Elisa struggles with her meager earnings, and traveling around Madrid constantly notes the many closed stores, desolate areas, and general sense of a city and nation lacking a sense of stability. Everything putters along, but is anything but thriving. Eventually, Elisa also struggles mentally, with panic attacks that overwhelm her, and literally paralyze her.

Among Susana's preoccupations is the making of elaborate maps, manually pasting cut-out images to create them -- even though a similar look could be achieved with a computer program. Elisa encourages her to show them, and very quickly Susana seems on the cusp of entering the rarefied art world -- success in the creative field that has eluded Elisa. It is at this point that Elisa feels it is time to free herself from Susana, as well, this long middle section of the novel concluding with Susana moving on.

A very short -- three page -- final part seems almost more an epilogue, jumping ahead some to Elisa's new, changed circumstances. It is in the form of a simple conversation, and sheds some new light on the preceding sections, too, suggesting that the stories are even more obviously Elisa's than their initial presentation suggested.

If her financial and employment situation is still a similarly: "stable instability", mentally Elisa finds herself more balanced again; as she reveals, she's found a means to get herself to: "Another mental space". Navarro also nicely finishes the book with this exchange, leaving the story -- and the questions it raises -- cleverly open-ended.

A Working Woman does perhaps start off and fall back all too easily on variations of madness -- but then this is a book that is set in an economy struggling against collapse and ruin (while still going through all the motions and keeping up appearances), and so madness, and how it unfolds and manifests itself, is an appropriate metaphor.

Appealingly, Navarro also doesn't fall back on the too-easy traditional forms of friendship and relationships -- though by stretching the concept so far at the novel's outset, she already blurs it in the reader's mind for the rest of the story. And while the pacing can seem odd -- including Germán getting rather lost in the shuffle -- the story is constantly propelling forward, and from the outrageous to the mundane, Navarro offers a good deal of good observation and invention. - M.A.Orthofer

When an author is lauded as a “relentless innovator” and a “meticulous explorer of the psyche’s most obscure alleyways,” it is easy to be skeptical. Those are strong endorsements, and a reader who enjoys a literary challenge knows well that a publisher’s promotional copy can be laced with hyperbole that often falls short of the mark. Yet, Spanish writer Elvira Navarro lives up to her billing with A Working Woman, newly released from Two Lines Press, one of the most peculiar novels I have read in a long time. Its strangeness is subtle, the tone is ever so slightly off, the structure unconventional, and the narrator’s account inconsistent. The opening section is unsettling, even off-putting, but sets the groundwork for an oddly metafictional tale that unwinds (unravels?) slowly to end with a coda that places the purpose and nature of the entire preceding narrative into question.

It is an uncomfortable book. A rare and original look at the complex dynamics of female companionship, the bonds and distortions of madness, and the desire to find and define oneself, creatively and personally.

Set in Madrid, during in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis, Elisia is a proofreader with one novel, an MA in Publishing and an unfinished PhD behind her. She is one of the working wounded, so to speak. She is lucky to have a job, but it has, over time, been reduced from a series of temporary placements to uncertain independent contract work for a publisher woefully behind with payments. She has already moved from an centrally located apartment to the barrio of Aluche in the southwest part of the city. As her financial circumstances become ever more precarious, she is faced with the prospect of renting her flat’s small second bedroom. When her friend Germán sets her up with Susana she does not know what to expect:

It was twelve thirty when she arrived. She wasn’t as I’d hoped, short and plump like a Hispanic mother, but the Nordic type: tall, blond, horsey, with a complexion the colour of something like raw silk. She was squeezed into a brown coat that came down to her ankles, and had a showy beige scarf around her neck. On her head was a green hat, with a swirl on one side like a flower. Weighed down by so much wool, she could hardly move, and her cheeks briefly glowed with two, perfect rosy circles. She was a bit ridiculous, particularly due to something that seemed to have its source in her nose, which, from the instant she crossed the threshold, appeared unpleasantly alert for any smell, the nostrils flared and quivering. It was such an eloquent gesture that, if I hadn’t previously committed it myself, I would never have considered accepting her as a roommate, and nor would she have taken the tiny room.

Their strained friendship sits at the core of A Working Woman. It is a relationship that seems, for the most part, to occupy an awkward space in the apartment, and in Elisia’s troubled imagination. She exaggerates Susana’s impressive Amazonian dimensions, and finds her elusive nature—her tendency to at once take over the shared rooms with her belongings but share little about her past or her daily life—disconcerting.

However, by the time Susana crosses Elisia’s threshold for the first time in the narrative, we have already been treated, no exposed, to a graphic portrait of the woman she was twenty years earlier when, in a period of marked mental instability, she took a gay dwarf lover to meet her particular sexual needs. The novel opens with what we are told is a story based on what Susana told Elisia about her madness. “I’ve added some of my own reactions,” she tells us, setting her own words apart in italics, “but to be honest they are very few. It goes without saying her narrative was more chaotic.” For nearly forty pages, the narrator records a bizarre tale of sexual obsession. It’s easy for a reader to wonder what they’ve signed up for. Later on, one begins to suspect, that the entire set up says more about Elisia than whoever Susana may be (or may have been). Especially as she begins to develop symptoms of mental illness herself and is forced into seeking treatment. The layers of madness and sanity overlap with metafictional questions of narrative intent.

A Working Woman is imbued with an intense restlessness and anxiety that extends beyond the characters’ own uncertainties into the world around them. The narrative excavates the raw edges of Madrid where the economic downturn has left its mark. Empty storefronts, abandoned buildings, construction projects halted midstream. Elisia’s nocturnal wanderings through the streets of her neighbourhood is refracted in the countless city maps her roommate constructs out of tiny magazine clippings. But the two women are ultimately on different trajectories in life. Their worlds collide, but their connection, mediated through Elisia’s oddly unbalanced narrative, is neither warm nor natural. It is not even clear that Susana, or at least Susana as presented, exists beyond the narrator’s literary aspirations—or her own delusions.

Confusing? Yes and no. Navarro’s language is direct and compelling. She creates vivid multidimensional physical and psychological landscapes. Her ability to evoke, through her narrator’s breakdown, the sensation of losing the ability to cling to reality is especially powerful, and one I recognize well from my own experiences:

I managed to alight from the bus—there was still no ground under my feet, and I had to support myself against the buildings. Then I sat down in a doorway and stayed there for I don’t know how long, until my sense of touch returned. It occurred to me that I was crazy. I formulated this thought ten, twenty times. Movement was painful. The lacerating rumble of traffic. The tense, high-pitched voices of friends chatting in doorways. The people walking behind me. Their breathing, their bodies, were too close. I was intolerable even to myself, wanted to tear my body to pieces.

From its unusual, attention-grabbing beginning to the curious short chapter that ends (or upends) the book, to read A Working Woman is to enter an altered hyper-reality, a place filled with strange, yet strangely recognizable, figures who leave you wondering where truth lies, and where stories within stories begin, and end. - Joseph Schreiber

Excerpt:

Except for the occasional weekend away, I usually left the apartment at night, which meant my encounters with the guys from the truck became almost routine. I continued to haunt the old prison, which had become a forest of rubble, a steep forest through which cockroaches scurried, and emitted a false glow at night—what in fact glimmered on the rubble were the lights from the Avenida de los Poblados. But it was as if those Dantesque fragments had light bulbs within them. I’d scramble through a hole in the wire fence and stay there quietly for a long time. I had the feeling that place was armor-plated, that it was enduring. The floodlights that had once picked out the shadows of the prisoners had been dismantled, and I didn’t dare explore the ruins for fear of falling. So I walked around them. Fear didn’t catch me; if large suburban parks like the Casa de Campo were being abandoned, with even the criminals going to places where they could get their hands on something more than hard carob beans and verbena petals, what was so different about that awkward heap of rubble? Before they pulled down the prison, I’d discovered that some of the cells—hardly much larger than six feet by four, and in which you couldn’t take two turns without feeling dizzy—were occupied. They had posted a security guard so the panopticon didn’t end up as a Romany village, but at night they turned a blind eye to a few solitary down-and-outs. In the occupied cells, I found the belongings of their nocturnal lodgers; everything had been extracted from dumpsters, which made the sight of overcoats and blankets on spindly hangers rather paradoxical. Before, I had gone to the prison with a girlfriend who was making recordings of the silence in the center of the penitentiary. If my friend had been with me now, it would have been impossible for her not to register the sounds of that deformed urban skeleton and its creaky joints. But, back then it was as if we were in a tomb, with the crypts blocking out the hum of traffic. And now she would also have been able to record the guys from the truck, whom I’d seen stop by the wire fence one day, negotiate the gap, and snoop around with strong flashlights. They didn’t see me. I was a long way away, quietly hunched down out of sight: there was a candy wrapper on the ground at my feet, and I could hear the chirping of insects. The third night I saw them playing daredevils on rotten planks; I realized they were looking for something that wasn’t cardboard. My discovery shouldn’t have been surprising, but then I know nothing of the criminal underworld. What I did know was certain materials were being stolen for resale on the black market. Copper mostly. Yet it didn’t ring true for me that, after years of standing empty, there would be anything of any value left in the prison. I don’t know exactly what they were pilfering, but expected to see them carrying long, sharpened sticks, weapons. I felt the need to stand up, and as I did brushed against some piece of corrugated iron that fell with a loud clang. The five Romanies turned, and shone their flashlights in my direction; my knees were shaking slightly, and although I very much wanted to hunch down again, I couldn’t even manage to breathe. They stood very still, making sweeps with their lights. The only things behind me were wire fencing, trees, and darkness. “Who’s there?” they shouted, followed by, “If you don’t get out of here, I’ll slash you.” Another one of them answered, “It’s a cat or something, dumbass. Let’s go.” The following day a number of front loaders turned up and cleared the area. What was left looked like a morass of gritty sand. I went back one last night, without being able to find the center of the lot, because I suddenly felt vulnerable, with too much city on either side to the horizon. I stayed close to the wire fence with its geometric design, and further on, to those weightless pincers that emerged from the darkness in the park. That night, I made my way home with a clear head, following a new route. I amused myself by zigzagging left and right, sometimes taking long detours because I liked going along unknown streets. I’m not sure just when I found myself in a stretch of neighborhood I knew.

Elvira Navarro, The Happy City, Trans. by Rosalind Harvey, Hispabooks Publishing, 2013

“I feel terrible. Although he doesn't say it, I know he had been hoping the whole time that I would explain it all somehow; but I can't explain it, because I don't understand anything.” These disturbing words, almost a distillation of the entire text, close the novel The Happy City by Elvira Navarro, who featured in Granta’s The Best of Young Spanish-Language Novelists issue in 2010.

The stories of Chi-Huei—a Chinese boy whose family has come to Spain in search of a better life—and his friend Sara—a girl strangely fascinated by a homeless man—comprise two separate yet complementary sections, presenting the reader with a detailed account of their life circumstances and the nuances of their perspectives: the genuine, as-yet untamed voices through which the book’s pre-adolescent protagonists negotiate the world around them, their initial astonishment finally turning to frustration as they gaze upon their dehumanized society.

A pre-teen’s first faltering steps towards sexuality, social pressures, the way polarized outlooks on life coexist at the core of the same family, those first experiences of disillusionment as we awaken into the adult world: these are some of the themes that Navarro lays out for her readers in order to reveal, with razor-sharp control, the constant duality that exists between the outward appearance of things and their inner reality.

Granta introduced the anglophone world to Elvira Navarro by naming her one of the best young Spanish language novelists in 2010, but Rosalind Harvey’s translation of her second novel The Happy City marks her first full-length work in English. The 2009 Spanish original earned both the Jaén Fiction Award and the Tormenta Award for Best New Author. Stepping into The Happy City, I felt that I had gone back to a former version of myself, empathizing with, even enduring, the pain of one of life’s inevitable metamorphoses. We find Navarro’s protagonists cracking through late childhood’s barriers into early adolescence, confronting the often formidable awareness that emerges as children naturally rebel against adult sentries whose control over their subjects conversely slips. The adolescents roaming this cityscape are presented in two separate novellas. One story relates the immigrant experience of a working class family through Chi-Huei, a young boy longing for maternal love and affection. The second is narrated by Sara, a comfortably middle-class, only child smothered by overly attentive parents. The city in question, Madrid, is the only character in the book whose growth is not measurable. More than merely comprising the story world, it connects the two tales by playing the role of an omnipresence holding the burgeoning adolescents captive in a determined quadrant of city blocks. Although not branded as Young Adult, it fits the bill.

The first novella begins with Chi-Huei in China. An unaffectionate aunt, “the old woman,” fosters him for a fee while his grandfather, step-grandmother, parents and older brother set up a Chinese restaurant and rotisserie in Madrid (13). They call the business Happy City, hopeful nomenclature. The family toils to establish itself and sends for the boy as the story unfolds. As the second son, he is expected to excel academically, and in turn, eventually pour this success into the business. Chi-Huei’s acrimonious receipt of and incongruity with this fate and the family who present it increase as he grows:

Navarro relates Chi-Huei’s story in the third person, juxtaposed with Sara’s first person account. This effect conveys the immigrant experience as marginalized, its characters revolving in a circle amongst one another. Sara represents integration for Chi-Huei, first presented to us as a conquest of his, more in terms of status and class than sexually, although inevitably, given their ages, sexuality is in play. Eventually Chi-Huei’s relationship with Sara sours and catapults him to a position of frustration that speaks to his dissonance with the mainstream. As the resentment between the two builds, “Naturally it didn’t even occur to him to cross the road and go to her house. He had never visited his friend during the week, and to cross this threshold now would have been to expose himself too much” (74). Thus, Navarro keeps him from assimilating, in spite of his effort. It is worth noting that Sara’s story only fleetingly mentions Chi-Huei, “the Chinese boy” as “something like my first boyfriend” (122). Sara details, instead, a disenchantment that crescendos to an inability to relate to the entirety of her peer group as her mania for a local vagrant consumes her.

Sara’s world is presented as a veiled, gated one with constraints thrust upon her by her parents every step of the way. “I am not allowed to play beyond the limit, and the most I do is to look over from the other side without stepping over the imaginary line my father drew one day with the tip of his shoe, a line I accept, although with a few small exceptions” (100). In response, she finds refuge in the most obscure, far removed location she can within the confines of the city blocks she is allowed to traverse: a French homeless man, an immigrant who, unlike Chi-Huei, rejects conformity with alacrity.

Sara and the homeless man study one another, seeking each other out with great care to attract no untoward attention. Navarro delicately and repeatedly brings the reader to the precipice of sexuality, in its most innocent form in Sara’s daily rituals. At a bus stop, she is “left behind in the race and am the last one in the line that forms at the steps. This period when I expose myself to the homeless man’s gaze seems eternal to me, and I’m also embarrassed to reveal how shy and awkward I am” (118). As a tenuous layer is shed, her bravado emerges:

Navarro dives headfirst into the embodied experiences of two disparate characters as she explores adolescence in the context of awakening. The enlightenment her characters achieve extends beyond their immediacy into the city, where the marginalization of outsiders is a line drawn in the sand, rousing in their young lives both angst and powerlessness. Harvey’s seamless translation of the lyrical prose places the reader in the middle of Madrid, stuck and frustrated, pushing boundaries but hitting walls. - Kate Lynch

Elvira Navarro, Rabbit Island. Trans. by

Christina MacSweeney. Two Lines Press, 2021

Combining the gritty surrealism of David Lynch with the explosive interior meditations of Clarice Lispector, the stories in Elvira Navarro’s Rabbit Island traverse the fickle, often terrifying terrain between madness and freedom. In the title story, a so-called “non-inventor” conducts an experiment on an island inhabited exclusively by birds and is horrified by what the results portend. “Myotragus” bears witness to a man of privilege’s understanding of the world being violently disrupted by the sight of a creature long thought extinct. Elsewhere, an unsightly “paw” grows from a writer’s earlobe; a grandmother floats silently in the corner of a room.

These eleven stories from one of Granta’s “Best Young Spanish-Language Novelists” are psychogeographies of dingy hotel rooms, shape-shifting cities, and graveyards. They act as microscopes fixed upon the regions of our interior lives we often neglect, where the death of God and the failures of institutions have given way to alternative modes of making sense of the world. They are cracked bedroom mirrors. Do you like what you see?

In my early teens, I realized fear was not something literature regularly made me feel. That said, I turned to certain dark narratives because the power of literature was never more present or more palpable to me than when a story made me feel profoundly unsettled. The stories in Elvira Navarro’s Rabbit Island aren’t easy to push into the horror box, but they are all deeply unsettling, and the uncertainties they evoke shine brighter against the backdrop of Navarro’s luminous prose.

Simply put, the eleven short stories that make up Rabbit Island are weird. They inhabit the interstitial spaces of everyday reality, dreams, and the impossible. Rabbit Island sets the mood early and gets progressively more bizarre while maintaining an uncanny atmosphere. “Gerardo’s Letters” is a tale about a woman staying at a decrepit hotel in a small town while trying to finally end a crumbling relationship. We all have been in this kind of relationship, but the aura of the hotel gets under our skin and the need to escape that exudes from Navarro’s writing somehow transfers to us. And that’s just the beginning.

After establishing that things here are not always what the reader expects them to be, Navarro takes a leap forward. In “Strychnine,” the main character has a paw growing out of her chest. Short and creepy, this story opens things up and lets readers know Navarro wants to do more than unsettle. She’s out to inject them with the horror of the inexplicable, and she does so with simple, precise prose:

The mannequins are more real than the vendor. She doesn’t hide the paw from him; his face pales as he watches it timidly reaching out its three toes toward him. He runs screaming out of the store. She races after him; her intention is not to frighten him, but to pay for the hijabs, although halfway into her flight she forgets the reason for the pursuit. All of a sudden the man seems like her prey. He’s thin, like a greyhound. But she can run faster.

The presence of a hotel becomes a bridge that ties the first and second narratives together. Animals and hunting for prey then become a bridge that leads to the third story, “Rabbit Island.” While there are no throwaways in this collection, there are standouts, and this story is one of them. The plot is deceptively simple: a man uses a canoe to explore a tiny island in the middle of Spain’s Guadalquivir River. He becomes obsessed with the island and eventually introduces rabbits into its ecosystem. What starts as an experiment soon morphs into strange, cannibalistic mayhem that turns the little piece of land into a bloody chunk of chaos right under the noses of the town’s residents.

In Navarro’s work, simplicity often becomes something much darker, and “Paris Périphérie” is a brief master class in how to achieve that. If the plot of “Rabbit Island” is deceptively simple, the plot of “Paris Périphérie” is almost nonexistent: someone can’t find a building. That’s it . . . and yet the story works. Experiencing a sense of desperation and inescapable dread while doing something normal—like walking the streets of a city—feels simultaneously outré and relatable, incredible but perfectly plausible.

“Notes on the Architecture of Hell” is another standout. The story of a younger brother dealing with the collapse of his older brother’s sanity, this is truly a tale in which the door to the impossible opens up and swallows the reader. Furthermore, it’s a narrative in which Navarro makes a powerful aesthetic statement. There are no answers here, so don’t ask any questions; just enjoy the strange ride.

The last tale I want to highlight is “The Top Floor Room.” It offers the perfect example of how Navarro writes believable characters with one foot in noir and the other in the fantastic. The main character here is a hardworking cook at a crappy hotel who starts to occupy the dreams of those who work with her and some of the people who stay at the hotel. Navarro dexterously moves from the microcosm of her protagonist’s dreams and memories to the macrocosm of the cold city and the weird places in which the woman eventually ends up sleeping. This journey between inner and outer worlds is present in almost every story in Rabbit Island. Navarro’s mastery of the trope speaks volumes about her storytelling chops and her understanding of how the human psyche operates, especially when faced with the impossible.

Some authors bend reality at will, and Navarro belongs to this group. Her stories are brave in the sense that they push against the formula present in most literary fiction by shattering reality time and again while also delivering mysterious tales that contain few answers and character development that wouldn’t feel out of place in genre fiction. Rabbit Island, which has been masterfully translated by Christina MacSweeney, is an outstanding introduction to Navarro’s boundary-breaking work. This is a brilliant collection in which gritty surrealism, poetry, noir, and horror collide, and the result will stick with readers like the image of a grandmother floating in the air in the corner of a dark room.— Gabino Iglesias

https://southwestreview.com/the-horror-of-the-inexplicable/

Elvira Navarro won the Community of Madrid’s Young Writers Award in 2004. Her first book, La ciudad en invierno (The City in Winter), published in 2007, was well received by the critics, and her second, La ciudad feliz (The Happy City, Hispabooks, 2013) was given the twenty-fifth Jaén Fiction Award and the fourth Tormenta Award for best new author, as well as being selected as one of the books of the year by Culturas, the arts and culture supplement of the Spanish newspaper Público. Granta magazine also named her one of their top twenty-two Spanish writers under the age of thirty-five. She contributes to cultural magazines such as El Mundo newspaper’s El Cultural, to Ínsula, Letras Libres, Quimera, Turia, and Calle 20, and to the newspapers Público and El País. She writes literary reviews for Qué Leer and contributions for the blog “La tormenta en un vaso.” She also teaches creative writing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.